History of HUUN

REVIVING A LOST ART

The History of HUUN Paper.

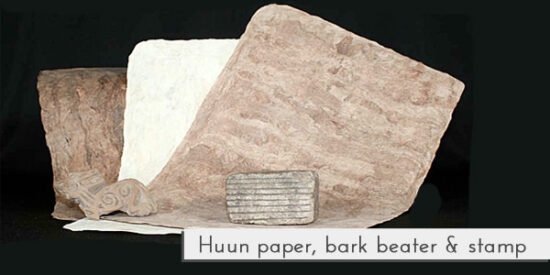

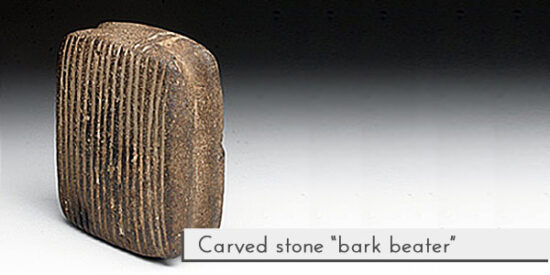

Hu’un is the Mayan word for ‘paper’ (also known by its Nahuatl name: “amatl” or “amate”). In the pre-Hispanic era, paper making was a thriving trade with entire towns exclusively engaged in its manufacture.

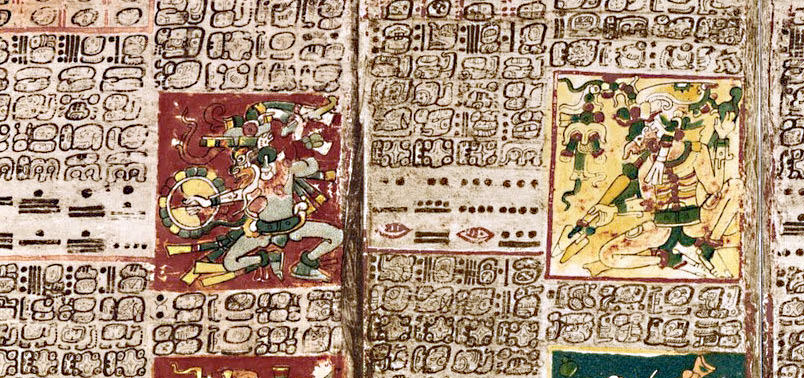

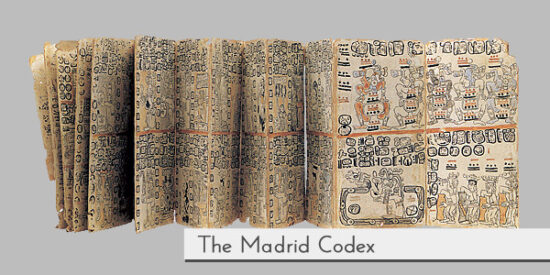

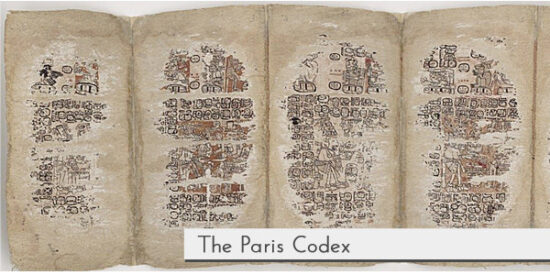

The paper was used to record their most valuable information on special folded booklets called “codices” (or “codex” in singular). Codices were used to document details about their religion, astronomy, agricultural cycles, history or prophecies.

In order to write on the codices, one had to be in touch with the gods and so, as such, the end products were considered sacred and were kept inside of temples or important civic buildings.

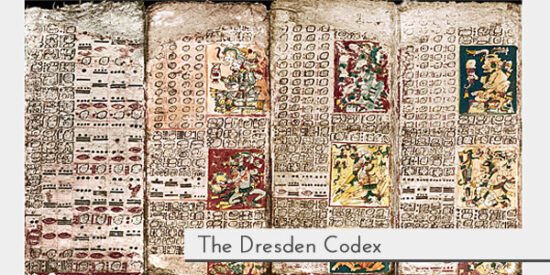

However, with the arrival of the Spanish conquistadors in the 16th century, missionaries systematically destroyed all of the texts for fear they would hinder the their efforts in converting the locals to Christianity. Sadly, today only three codices remain and they are named for the cities in which they were discovered; The Dresden Codex, the Paris Codex and the Madrid Codex. Though how they got to these cities in the first place remains a mystery.

The art of paper-making, once a wide and useful tradition, was lost by the turn of the 17th century and only a handful of artisans kept up the tradition.

If you are interested to know more about the specifics of each codex and the content contained within, there are several indepth websites you can visit: